The next eighteen months will tell us whether the “AI factory” narrative hardens into industrial reality or dissolves into a capital-spending hangover. At the center of the chessboard are three levers that will shape who captures economics in 2026: Nvidia’s control over accelerator platforms and its increasingly strategic dance with Arm, AMD’s MI325X memory-heavy refresh designed to ease the training/inference bottleneck without ripping and replacing full racks, and Broadcom’s silent—but decisive—grip on the connective tissue of AI networks from Ethernet switch silicon to optics-ready roadmaps. Read the supply chain through those levers and the story is about bargaining power, software lock-in, and where the bottleneck migrates next.

Nvidia’s long game is to keep the highest-value compute layers scarce and integrated: CUDA as switching cost, NVLink/NVSwitch as intra-cluster preference, and a move to Arm-based platforms (from Grace-class CPUs to customized boards) that lets it tune memory bandwidth and coherency around its own accelerator cadence. The licensing dance with Arm matters less as courtroom drama and more as ecosystem leverage: the more Arm defines the instruction substrate in AI servers and edge inference boxes, the more Nvidia can shape platform assumptions—from compiler targets to NIC/DPUs—without ceding the software moat that keeps rivals expensive to adopt. If Nvidia maintains that gravitational pull while rationing top-bin parts, gross margins north of 70% on accelerators remain defensible even as volumes climb.

AMD’s MI325X is the pragmatic counter. It is not a theology; it is a memory play. The headline is capacity and bandwidth—HBM3E-rich configurations that give model teams the two things they are paying up for in 2025–2026: fewer tensor-parallel shards and less orchestration pain across nodes. If AMD can ship MI325X in real volume, validated in mainstream frameworks with robust ROCm improvements, the buying center calculus shifts from “Do I defect from CUDA?” to “Can I buy 20–30% more usable tokens per watt per dollar this quarter?” That is exactly how incumbency is eroded: not by ideology, but by a more elastic supply of high-capacity memory footprints that hit acceptable time-to-train. In that world, AMD’s blended accelerator margins in the high-60s to low-70s are plausible, but contingent on HBM supply and multi-vendor boards shipping on schedule.

Broadcom, meanwhile, is the understated kingmaker. AI factories are networks that happen to do math. Ethernet is winning mindshare in at-scale training clusters because it lets operators use familiar tooling while vendors layer on congestion control, in-network compute features, and co-packaged optics over time. Jericho/Tomahawk-class silicon, merchant optics, and increasingly tight NIC-switch co-design give Broadcom leverage that looks a lot like a tollbooth on every incremental rack. As AI clusters tilt toward 1000+-GPU fabrics with ruthless east-west traffic, the willingness to pay for predictable completion times keeps networking margins structurally elevated. Unless InfiniBand mounts an unexpected resurgence via turnkey bundles, Broadcom’s AI networking gross margins in the mid-60s feel durable.

The bottleneck—and thus the profit pool—will keep sliding between compute, memory, and network. In 2023–2024 it was accelerators. In 2025–2026, memory capacity and network determinism share the throne. HBM supply discipline by SK hynix, Samsung, and Micron is the quiet variable that decides whether accelerator vendors or memory vendors capture the incremental dollar; tightness favors GPU/accelerator ASPs, glut pushes more value to buyers and compresses chip margins. ODMs and OEMs, even with liquid cooling and high-power chassis differentiation, will remain the thinnest slice; their upside is volume and services, not price.

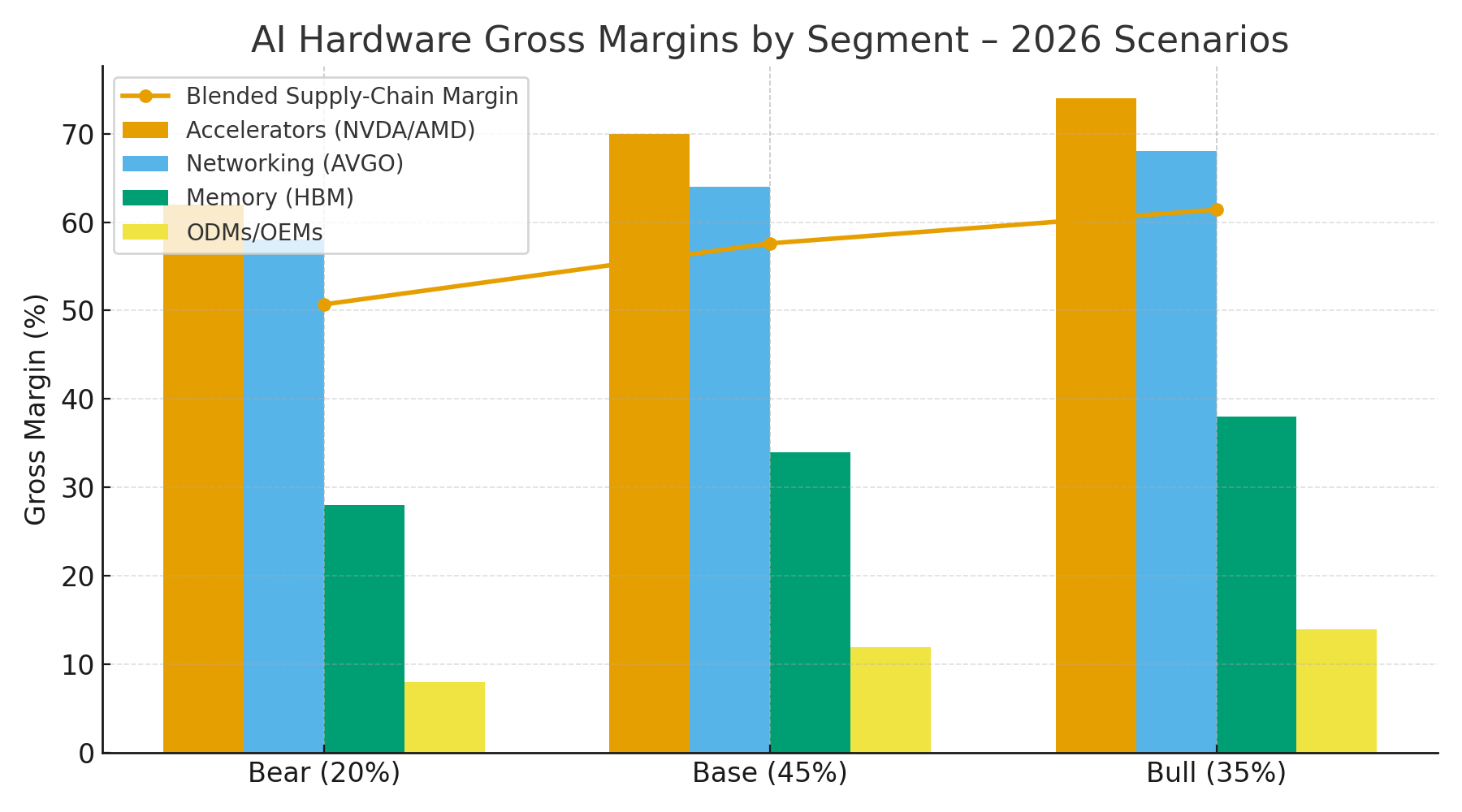

To anchor the debate, here is a probability-weighted view of 2026 gross margins by segment, framed around where the bottleneck settles and how successfully vendors enforce moats. In the bear case (20% probability), buyers regain leverage as supply loosens and model growth slows; accelerators slip to ~62% GM, networking to ~58%, HBM to ~28%, and ODMs to ~8%, yielding a blended supply-chain margin near ~51% given a revenue mix weighted 55% accelerators, 20% networking, 15% memory, 10% ODMs. In the base case (45%), demand stays strong but less frantic, multi-vendor validation lands, and supply improves without collapsing pricing; accelerators hold ~70%, networking ~64%, HBM ~34%, ODMs ~12%, pushing the blended margin to ~58%. In the bull case (35%), parameter growth and inference proliferation outrun fab expansions, top-bin parts remain scarce, and software moats harden; accelerators rise to ~74%, networking ~68%, HBM ~38%, ODMs ~14%, and the blended chain prints ~61%—an environment where free cash flow compounds quickly for chip and switch vendors while buyers chase delivery slots.

The strategic takeaways are crisp. First, software gravity is still the richest currency: whichever camp reduces developer friction while keeping portability costly will harvest margins even if BOM costs rise. Second, memory dictates topology; any vendor reliably shipping more HBM per accelerator wins disproportionate wallet share because it reduces cluster count and operator complexity. Third, deterministic networks are worth a premium when fine-tuning and retrieval-augmented inference become 24/7 workloads; Broadcom’s ability to sell “predictability per dollar” is the quiet cornerstone of its AI lead. Finally, the 2026 margin winner is not a single logo but a bundle: accelerators with abundant HBM, Ethernet switching with mature congestion control, and tight NIC-host integration—sold into buyers who cannot afford to lose months to integration risk.