The humanoid robotics race has shifted from speculative research projects to a high-stakes industrial contest. For decades, humanoids were stage curiosities—machines that could walk, wave, or climb stairs but not justify their cost beyond demonstrations. Today, however, the intersection of labor shortages, demographic aging, and leaps in AI and control systems has catalyzed a new seriousness. Global manufacturers, logistics giants, and capital-heavy startups are converging on a vision: robots that look and move like humans, capable of slotting into environments built for people without retooling factories or warehouses. The bottlenecks remain hardware and cost, but the industry is finally organizing around a credible trajectory for breaking through.

At the front of the pack is Agility Robotics. Unlike companies still perfecting flashy prototypes, Agility has committed to manufacturing scale through its “RoboFab” in Salem, Oregon, with an explicit run-rate goal of 10,000 Digit humanoids per year. This is not about science fiction—it is about intralogistics tasks like case handling, tote moving, and routine shop-floor assistance. Amazon’s public testing of Digit underscores why: fulfillment centers depend on repeatable, labor-intensive workflows, and if a humanoid can reliably offload even a subset, the ROI is immediate. In that sense, Agility’s lead is defined not by acrobatics but by the unglamorous consistency required in a factory context.

Tesla, by contrast, has dominated headlines with Optimus. Elon Musk frames the project not as a niche industrial tool but as the next great consumer platform, even hinting at eventual household utility. Tesla’s advantage lies in its automotive-scale supply chain, integrated AI stack, and ruthless cost-down culture. Musk has repeatedly floated a $20,000–$30,000 target price at scale, which, if achieved, would radically alter the economics of adoption. To be clear, that price is not reality today, but it sets a benchmark investors and competitors alike take seriously. Tesla’s real differentiator is not that Optimus can perform tasks others cannot, but that Musk is pursuing “physical AI” at consumer-electronics cost curves, reframing humanoids from exotic prototypes into potential mass-market appliances.

Boston Dynamics, now owned by Hyundai, continues to hold the crown for technical capability. The fully electric Atlas demonstrates unmatched mobility, dexterity, and dynamic manipulation—leaping, flipping, lifting, and recovering balance with uncanny fluidity. Yet Boston Dynamics has always straddled the line between research showcase and commercial product. Spot, its quadruped, sells in meaningful numbers, but Atlas remains aspirational. Hyundai’s manufacturing empire gives Boston Dynamics the option to pivot toward scaled production, but for now, the company primarily leads as a technical benchmark.

Meanwhile, a fast-rising group of challengers is pushing hard. Figure AI has secured partnerships in the automotive sector, emphasizing humanoids as factory labor supplements. Apptronik, with its Apollo platform, is explicit about targeting sub-$50,000 pricing once scaled, positioning itself as the pragmatic cost leader. Sanctuary AI in Canada and 1X in Norway emphasize teleoperation and cognitive architectures, arguing that useful humanoids must begin by leveraging human oversight to bridge the gap between AI competence and real-world unpredictability. In Asia, China’s Unitree and Fourier Intelligence are playing a different game: making humanoids directly available at list prices in the $90,000–$150,000 range for research and early adopters, while also introducing smaller, cheaper variants. Unitree’s G1, for instance, has been promoted around $16,000, a striking price for a functional humanoid platform. These companies lead less in industrial contracts and more in democratizing access, ensuring thousands of researchers and hobbyists can get their hands on humanoid form factors.

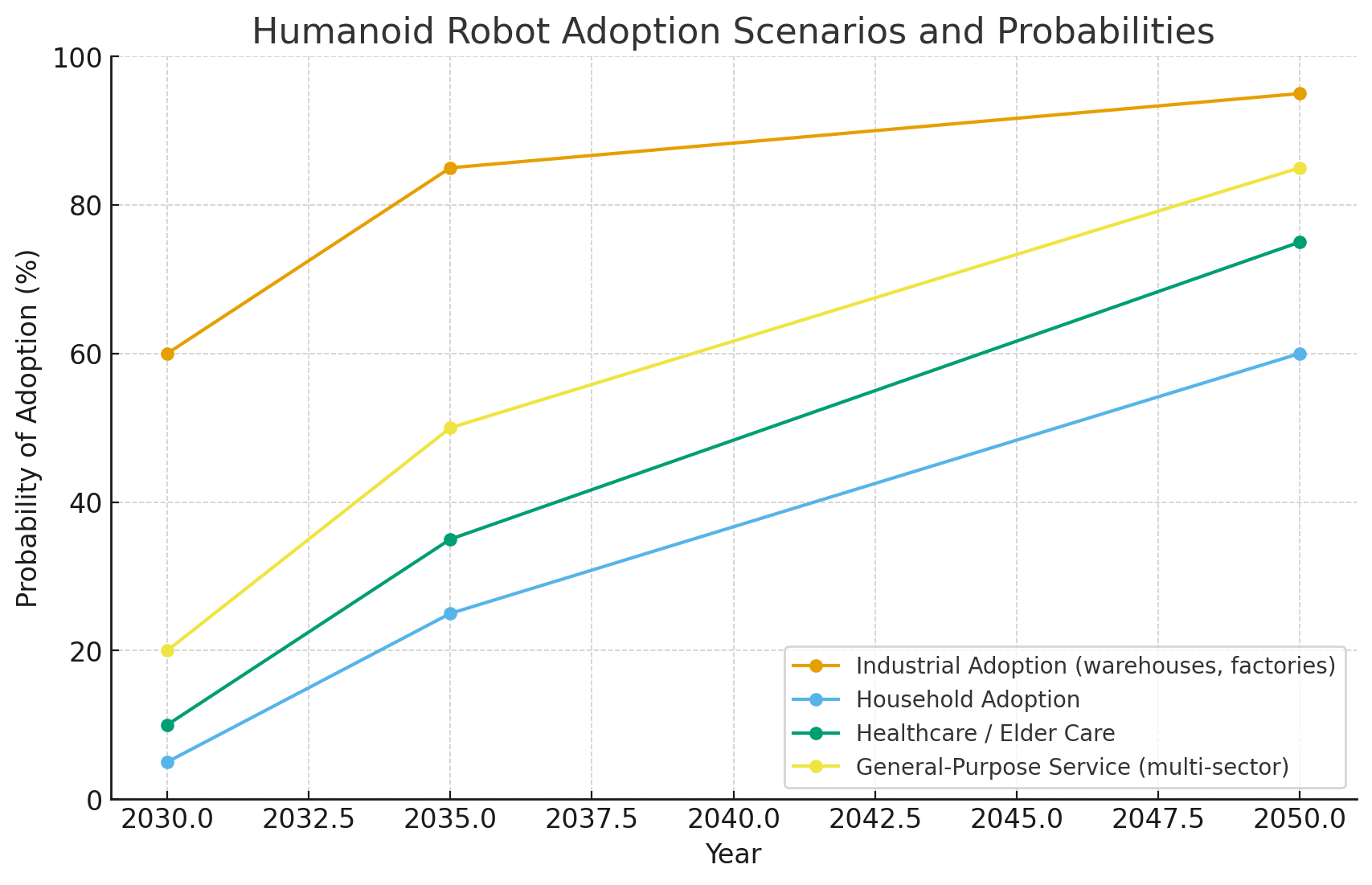

The market sizing reflects this diversity of approaches. Goldman Sachs projects a $38 billion humanoid market by 2035, driven by roughly 1.4 million units shipped. UBS pushes further, suggesting hundreds of millions of working units by 2050 as labor shortages and demographic aging accelerate adoption across manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, and even domestic settings. Near term, the wedge is clear: humanoids will proliferate in warehouses, factories, and logistics hubs, where the cost of labor is high, tasks are repetitive, and uptime is maximized across multiple shifts. Only once those workflows stabilize and costs fall further will household adoption become more than an aspirational marketing line.

The economics of adoption can be distilled into one brutal question: can a humanoid deliver productive hours at a lower effective cost than a human worker? In the United States, warehouse associates earn $18–$23 per hour base pay, often rising to $30 or more once benefits are factored. Across all industries, the Bureau of Labor Statistics pegs fully loaded employer costs near $45 per hour. For a robot to compete, it must achieve a per-productive-hour cost below $15–$20, to justify both the integration risk and capital outlay. If a humanoid can deliver 3,000–5,000 hours of work annually, with a five-year service life, this translates into an acceptable acquisition range of roughly $75,000–$200,000, depending on service contracts and utilization. The lower bound of that spectrum is where adoption inflects.

This is why Tesla’s $20,000–$30,000 aspirational price point and Apptronik’s sub-$50,000 target matter so much. At those levels, paired with reliable uptime and service models that keep operating costs under $5–$10 per hour, humanoids would undercut human labor in high-wage markets. The trigger for widespread rollout is not dazzling demonstrations but mundane finance: when the total cost of ownership yields single-digit or low-teens dollars per productive hour, large enterprises will scale orders from dozens of units to thousands. In lower-wage geographies, adoption will hinge either on ASPs falling toward $20,000–$40,000 or on robots being flexible enough to consolidate multiple roles into one asset.

The result is a fragmented leadership landscape. Agility Robotics leads in scalable industrialization with Digit and a credible volume plan. Tesla leads in ambition and cost-down narrative, setting the tone for investor and public imagination. Boston Dynamics leads in technical dynamism and dexterity. Unitree and Fourier lead in accessibility, pushing humanoids into labs and startups globally. And capitalized entrants like Figure, Apptronik, Sanctuary, and 1X are racing to carve domain-specific niches that can bootstrap them into broader platforms.

The market itself is less a monolith than a series of expanding concentric circles. The inner ring is logistics and intralogistics, where tasks are structured, environments are controlled, and ROI math is clearest. The next ring is general manufacturing, where humanoids will need more dexterity and broader task flexibility. Further out lies healthcare, elder care, and domestic service—sectors with massive addressable demand but far higher tolerance requirements for safety, perception, and social interaction. The outermost ring, consumer adoption, remains decades away, not because software lags, but because cost and reliability must fall orders of magnitude further.

Ultimately, the decisive moment will not arrive with a viral demo but with a boring financial report: a Fortune 500 company quietly showing that humanoids lowered labor costs by 20% in a warehouse or factory, while sustaining uptime comparable to human teams. Once that threshold is crossed at scale, the market’s S-curve will steepen. Every roadmap in the sector now orients toward the same target: consistent sub-$15 per productive hour. When ASPs settle between $20,000 and $50,000 with industrial reliability, humanoids will no longer be futuristic novelties—they will arrive by the pallet.